My research residency confirmed again how the direct, unfiltered experience of examining an artifact creates a moment of connection, empathy, wonderment and expansion similar to the moments of shared experience in a live performance. A chance for a fuller narrative opens up, independent of interpretive trends, making way for me as a dramatist to offer general audiences new emotional, creative identifications and understandings, experienced through the electricity of shared discovery.

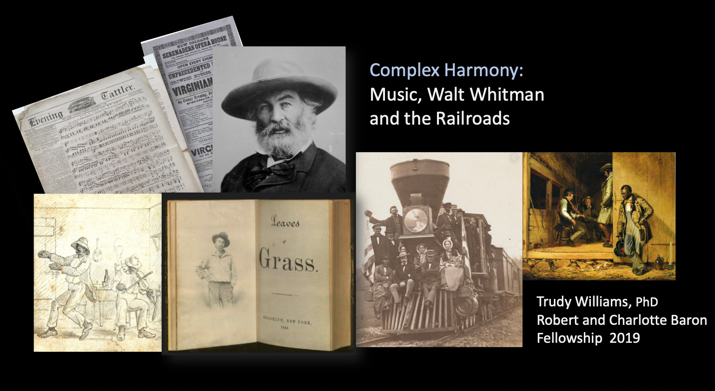

During my month long residency at AAS as a Fellow, I began primary research for "Complex Harmony: Music, Walt Whitman, and the Railroads", a theatrical program I am writing that combines a research-based narration, musical performance, theatrical roles, and large scale artifact images to give general audiences factual and interpretive connections between the soundscape of Walt Whitman’s 19th century America, the music he was passionate about, the influence of his musical interests on his poetic voice, and the social and cultural impact of the railroads, which he loved. Conveyed in this experiential tour will be elements of the simultaneous contractions and expansions that characterized aspects of the poet’s evolution and the entwined, often conflicting 19th century American cultural and social rail-provoked and rail-enabled transformations.

As we do now, Whitman’s America faced unsustainable structures and conditions with unimaginable solutions, yet moved forward, creating a legacy of gifts and burdens. Intended as entertaining and informative (with a sing-along component and Q&A at the end), the program will end with an invitation to consider that the gifts seeded in the 19th century come from a still present continuity of individual and collective strengths that we can choose to draw on as we face our times’ critically urgent needs. Embedded in the program’s conclusion are thoughts on the role of artifacts and our continued support for their care and access as an essential component for our humanity, contributing to what informs the decisions we make today that become our future tomorrow.

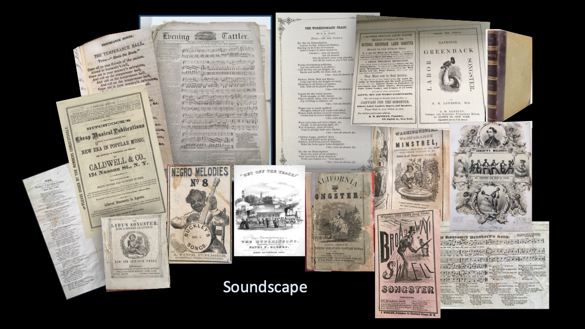

Soundscape: Musical activities in the aural tradition and sheet music beyond the parlor

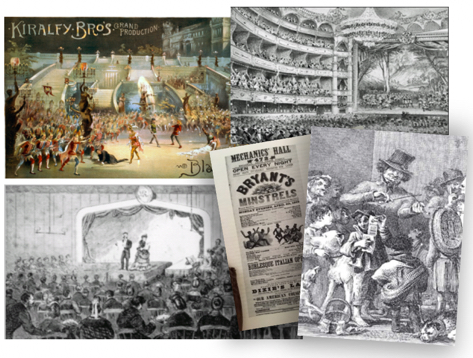

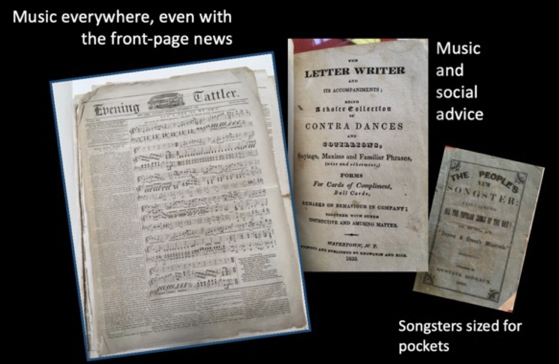

The many forms of the 19th century soundscape reflect the inter-racial and multi-ethnic borrowings and cultural border-crossing exchanges between and among the vernacular arts culture, as well as the economic and educational forces that sought to establish formal musical literacy and related goods and publications for popular consumption. Boundaries of “high” and “low” culture, what and who ‘mattered’ or not, solidified. Improvements in publishing and distribution, and the ability to build larger permanent performance venues, aided the growing commodification of culture. With equal force, vernacular cultural engagements with its participatory enjoyment and creativity, continued, especially in the singing and dancing that was so much a part of everyday life.

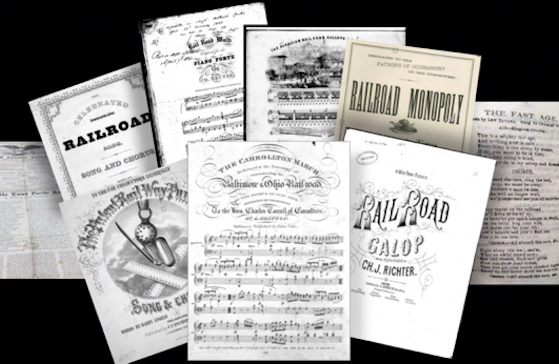

Railroad Music, Songsters and Broadsides

Music is distinctive in every period of our history. Whether created and experienced in the aural tradition or publication, it is a reliable portal into the personal, social and civic experiences, interests, hopes, fears, failures and pride of the prevailing historical and cultural ecosystem. Sheet music, songsters and broadsides are some of many cultural forms that attest to the massive impact of the railroads on American life.

Some of my favorite artifact encounters were with what people used, held in their hands and carried in their purses and pockets.

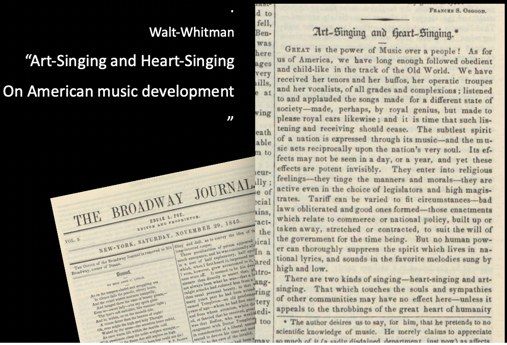

Whitman’s 1845 Statement on American Music

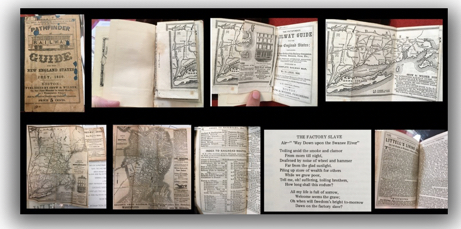

Railroad Guides

The pocket-sized Railway Guides were published weekly. The new technology of railroads changed the timing, pace, and in many cases, place, of people’s lives, while publishers created an association between depot timetables, social advice, editorials on hot issues, poetry, lyrics, pull out maps, advertisements and other information promoted as essential to have at hand, in your pocket or purse. Much like our smart phones today.

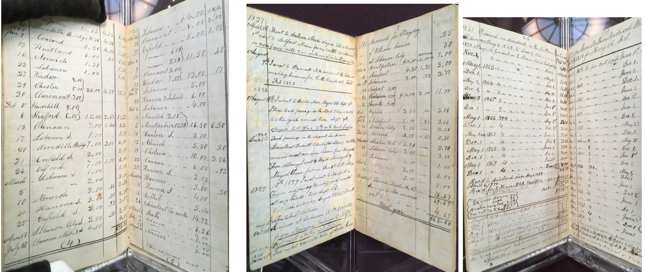

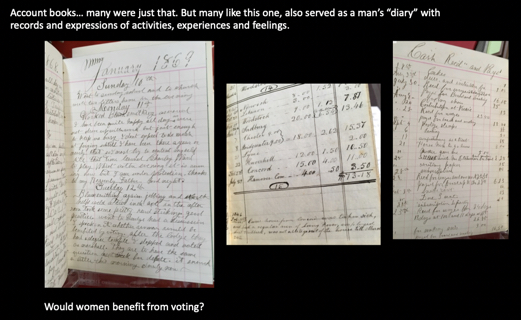

Account Books

The Fiddler’s Account Book was a consistent record of work activity (teaching and performing) and expenses (travel both local and away, instrument care, lessons). These images provide a look at his life as a ‘culture worker’: the pattern of weeks of travel for musical work followed by days sick in bed, and the cycle begun again.

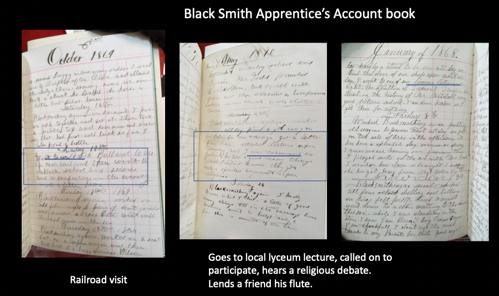

Apprentice Blacksmith’s Account Book. Click the image on the left to view the October 1869 entry in the Account Book.

In the Reading Room

I arrived at AAS thinking I would spend a precious month happily free from quotidian obligations, immersed in stellar archival material, taking notes and pictures, watching my program content map and scripting evolve as information and insights build up. I’d enjoy my fellow researchers, sometimes directly, sometimes just in our unspoken but energizing shared, parallel absorption in the reading room. All this happened, and it was great.

What I had not foreseen, and what added to the depth and richness of my time at AAS more than I could have imagined, was the constant support, validation, collaboration, new exposures and chances to expand my investigations that I received from many sources. In an initial orientation meeting, Nan Wolverton, Director of Fellowships and the Center for Historic American Visual Culture said, in effect, ‘don’t be surprised if you’ve come in looking for one thing and your time here leads you to change things!’ It was a great reminder to be less concerned about producing a ‘product’ at the end of four weeks and focus more on what I can find out and where it takes me. All during the month, Nan was a continuously validating presence in the reading room, regularly stopping by to ask how things were going, offering advice and guidance in response to any question or help I needed.

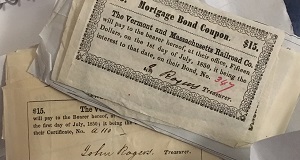

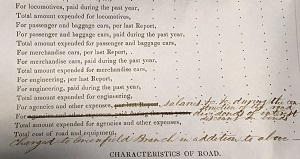

Within the first few days, like all Fellows, I gave a brief description of my project at a meeting with the Curatorial staff. During the weeks that followed, they became creative knowledge collaborators, bringing to my attention via conversation and/or materials, information and items in the collections I might find worthwhile to explore but might not know to look for. Especially helpful were Ashley Cataldo, Lauren Hewes, Elizabeth Pope, Kimberly Toney, Laura Wasowicz (the emergence of railroads in children’s literature morality tales and book illustrations), Kevin Wisniewski (Walt Whitman; railroad development), Nan Wolverton and Dan Boudreau. All staff on the desk were always incredibly helpful. A tutorial by Amy Tims on search techniques specific to AAS collections was invaluable. I had a fascinating time when one of the Curators, Ashley Cataldo, knowing of my interest in the railroads, invited me to join her as she opened a newly received large wooden box of railroad records for the first time.

Click the images above to view details of the railroad records found in the box.

Rails brought a new timescape to America. With it came fast ways to spread counterfeit currency.

The month also brought unique settings for learning and exchanges: the AAS public programs and Curator programs; weekly gatherings where Fellows at the culmination of their residency presented their project progress to date to the other Fellows and AAS staff, who responded with comments and insights. These sessions, headed up by Distinguished Scholar in Residence Karen Sanchez-Eppler, were supportive, illuminating and fun. I came away from my presentation with suggestions for additional areas to explore and potentially include in my program, most notably: the foundational impact of the steam engine (Jim Moran), the railroad’s impact on the lives of people with disabilities (Don James McLaughlin), and Chinese immigrant participation in the vernacular and organized cross-cultural exposure and engagement in the arts (Rachel Miller).

Being a Creative Fellow among the Fellows: I found a welcoming, curious community of scholars at varying points in their careers with fascinating projects in progress, in a beautiful house organized and maintained in a way that made for a very comfortable shared living space with many options for both group interaction and privacy. Everyone was curious to know what my project was about, what was I looking for and why. There were some great moments when people shared with me something they came across while doing their research in the reading room that they thought might be of interest to me. One of those times led me to the Account Books belonging to a fiddler and a blacksmith, which conveyed in their own voices a unique look at aspects of their work and life.

My time at AAS connecting directly with artifacts that people in Whitman’s time used, saw, read, kept, collected, wrote with, read out loud from, and more, gave me a richer sense and understanding to draw from for scripting the theatrical roles, Whitman’s included. I decided to move more of the narrator’s content into the actor’s voices, conveying stories and perspectives of ‘ordinary’ people in their various roles to express the historical and cultural realities of their lives. Despite all the problems, Whitman’s 19th century was also a time of great play and experimentation. Both those social strengths will also surface in the program’s performances and artifact images.