American Antiquarian Society

185 Salisbury Street

Worcester, MA 01609

United States

In an age when we are hyperaware of global warming, we tend to speak of ecological crises in global terms, representing environments through international comparison and webs of interdependency. Yet it is easy to forget how recent this development is, when just two decades ago catastrophes such as pollution were framed with specific attention to immediate contexts. Even the idea of shared national environmental concerns is relatively recent, suggesting that we should pay attention to how writing before the twentieth century reflected a sense of place. In this seminar, we will look at prints, manuscripts, and illustrations from the early American colonies and early republic that articulate such a sense of place. Authors of these texts certainly faced no lack of environmental problems, but these were often tied to spiritual and aesthetic questions. Often such writing had only an indirect relation to political action, because writers at the beginnings of the Anthropocene had considerably less confidence in their ability to control their environments. While ecocritical approaches to cultural history have tended to prioritize land, we will especially consider water which can reinforce and unsettle our sense of place.

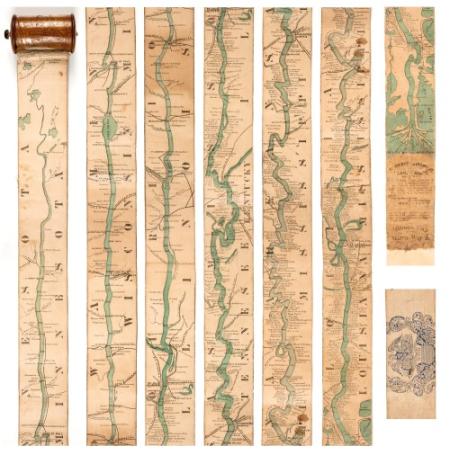

We will examine the construction of sewers, canals, and waterworks; forms of oceanic and riparian commerce such as the ice trade; the development of irrigation and river diversion; Indigenous perspectives on water rights; imaginative literature about islands; and the ocean’s economic importance as vehicle of transportation and eventually a source of energy. Materials studied will include illustrations such as harbor views and seafaring maps, but we will also look at travel writing, fiction, and children’s literature that reflect various kinds of ecological awareness. We will also consider how book production, such as paper and ink, reflect developments in environmental history. As we take account of what scholars have called the “blue humanities”–the study of the relationship between land cultures and water–we may find that the inevitable signposts in the development of American ecological consciousness are no longer Emerson’s Nature (1836) and Thoreau’s Walden (1854), but also that we need to write a cultural history better attuned to oceans, rivers, and other waterways.