Click the images above to view the Algonquian Bible in more detail. Read an excerpt of Diane's ma

When I applied for the Baron Fellowship in Creative Writing, I had a manuscript-in-progress called, Quadrille, a four-part work at the junction of Christianity and the eastern Native American. For many years I have given voice to those who did not have a chance to speak, or whose words were not recorded— Pushing the Bear, the 1838-39 Cherokee Trail of Tears. Stone Heart, Sacajawea and the 1804-06 Lewis & Clark expedition. The Reason for Crows, Kateri Tekakwitha, a 17th century Mohawk, converted by the Jesuits.

At the American Antiquarian Society, I wanted to look at the Native experience with early Colonists, especially Reverend John Eliot. The other three sections of Quadrille were finished— “I, Tatamy,” a Lenni-Lenape interpreter for the missionary, David Brainerd in the mid-1770’s. “The Unsettling,” 1807-35, the Eastern Cherokee in the years that preceded Removal. “The Conversion of He Goes First,” a Cheyenne prisoner at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida where the last of the Plains warriors were taken, 1875-1878.

The fourth section, “New England Indians,” was not written, though it would come first in the manuscript. At AAS, I also worked with the order of the four sections, and decided to list them chronologically.

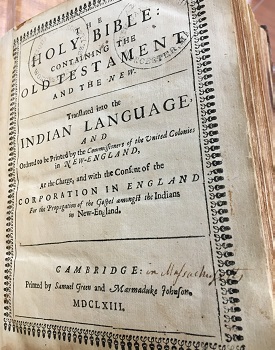

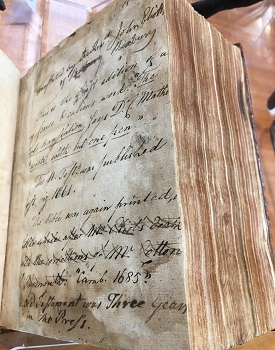

Upon Reverend John Eliot’s arrival in the Colonies in 1631, he learned the Algonquian language and began to translate the Bible. He worked fourteen years translating scripture. The Algonquian Bible was published in 1663. Several Native men helped with the translation, but they received little recognition. At AAS, I asked Kim Toney for the names. Actually, I asked Dan Boudreau who led me to Kim because much of the library was closed in the pandemic. I then decided to focus on four men: Wowaus, or James Printer (Nipmuc), John Sassamon (Massachusett), Cockenoe (Montauk), and John Nesuton (Massachusett). I used their first-person narratives as a road into the turbulent project, not only translating the 783,137 words in the Bible, but also clarifying biblical concepts alien to Native.

I knew I had to narrow the scope of research. It was the hardest part of the fellowship. There is so much rich information in the AAS holdings. I had to decide on the focus, eliminating so much other material I would love to have studied. I also reread the three sections of Quadrille for continuity— the early Cherokee, Tatamy or Moses Tenda Tauta-my, and David Pendleton Oakerhater, the Cheyenne prisoner who became the first Native Episcopal priest— so that the new section would fit with the other broken- narrative style of writing. I sat at the library table in the reading room in my mask, separated from a few other fellows that had been allowed during the pandemic. My greatest day was when Elizabeth Pope brought the 1663 Algonquian Bible to my table.

For a month I read the research materials such as Kim Toney’s online exhibition, From English to Algonquian. I read books, many of which Toney recommended. I made note of fragments or retrievals from history. I thought how to place them together in an unconventional structure. It was a creative artist fellowship and I could experiment with the research information. Eventually, I felt the momentum to enter the missing parts of history with first-person narratives of what it was like for the four Native men at the table with John Eliot, torn between a spiritual mission and the underlying thought of becoming a traitor to one’s Native way of life.

Gratefulness to AAS.