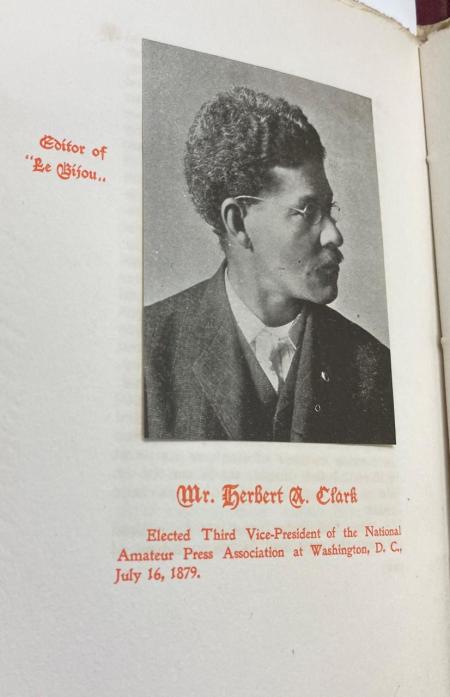

A photographic image of Herbert Clark from the 1904 edition of Ink Drops.

Le Bijou, published August 1878 to at least June 1880, was edited and largely written by African American amateur journalist Herbert A. Clark (1857 or 1858-1921). The son of African American educator, periodical editor, and socialist Peter Humphries Clark (1829-1925), Herbert Clark contributed to the professional periodicals Boys of New York, Boys' Own, and Wide Awake. According to his 1904 essay "A Drop of Black Ink" written for the amateur periodical Ink Drops, "From these boy papers of the days of 1874-5-6, I learned of the publication of amateur papers by the youths of America. Yet, the first amateur paper I ever saw was published by two colored boys at Frankfort, Kentucky, their father being the editor and publisher of a colored weekly paper." (Ink Drops (June 1904), p. 100). Starting out as a "puzzler," he contributed puzzles to these papers as well as to the amateur Lexington, Kentucky paper The Juvenile Weekly in 1877. The following year he became an associate editor of the Evansville, Indiana Amateur Argus. Encouraged by white puzzler Correl Kendall, Clark launched his own amateur paper Le Bijou in August 1878. Although a polished and spirited writer, Clark attended but failed to graduate from Gaines High School in Cincinnati. (Source: Nikki M. Taylor, America's First Black Socialist: The Radical Life of Peter H. Clark (2013), p. 73.) Apparently, he put his energies into contributing puzzles and written pieces to these various papers before starting Le Bijou. In late 1878 Clark left Cincinnati to teach school in Rodney, Mississippi, apparently while attending Alcorn University in nearby Lorman, a Mississippi state land grant university for African American men. (Source: "Our Colossal Chaos," Idle Hour, Apr. 1879).

Le Bijou was a twelve-page, twenty-four column paper issued six times per year. It was printed for Herbert Clark by his friend Edwin Booth Smith (1858-1936), a white Cincinnati amateur who became a dentist in Cincinnati and later worked in New York, N.Y. Although Clark left for Mississippi several months after he started the paper, he continued to issue it from Cincinnati at least in part because his sisters Consuelo Clark (later Consuelo Clark Stewart, 1860-1910) and Ernestine Clark (later Ernestine Clark Nesbit, 1855-1928) regularly contributed to the paper. In particular, Consuelo provided regular commentary on current developments in amateurdom in her column "Consuelo's Corner." She was also a gifted essayist and short story writer. Read her Halloween prank story "The Last Supper" by accessing two pages (first page and second page) of Le Bijou. An excerpt from her essay "Faith" is available at the bottom of this page.

The subject of race took center stage in the July 1879 issue of Le Bijou. It covered the aftermath of Herbert Clark's election as a vice president of the National Amateur Press Association at the recent national convention in Washington, D.C. As a result, a group of white southerners led by North Carolina amateurs including Edward A. Oldham threatened to secede from the NAPA. Oldham published a fiery editorial of Clark's election in his paper Odd Trump reprinted by Clark in Le Bijou; here is an excerpt:

"A Southern boy, when attending Northern conventions, would feel slightly out of place to find alongside of him colored members. This is the main thing, it matters not so much about their running amateur journals, this we cannot object to, but when it comes to their being admitted into active membership of our principal association then it is time for Southern amateurs to raise a hue and cry to prevent it." Access an image of the entire article.

Oldham eventually became a prominent newspaperman in Winston-Salem, N.C., and a driving force behind the publication of Truman J. Spencer' History of Amateur Journalism (1944, 1957). As a result, Clark's election is completely omitted from the History of Amateur Journalism. A nearly contemporary description of Clark's election is described in Richard Levan Zerbe's Guide to Amateurdom (1883).

In response to Oldham's racist remarks, Herbert Clark writes,

"In the Republic of Letters there has never been any distinction save that of merit. From the blind beggar, Homer, down the ages through Aesop and Terence, the slaves, to Dumas, the mulatto, the only credential asked or given, was that of merit. … As for us, we are Americans, Our ancestors, free colored men, fought with Washington at Brandywine and Germantown; others sailed with Perry at Put-in-Bay and marched with Harrison in Canda. Whatever glories were gained for the American name in those days and in those struggles, we share; whatever rights were earned, we inherit." Read Clark's full remarks by accessing images of two pages (first page and second page) of Le Bijou.

Fellow Ohio white amateur Arthur J. Huss (1861-1892) flamboyantly denounces the white southern amateurs' clamor for their self-stated "Civil Rights":

"When a set of ass-like youths who haven't brains enough to stick a pin in and whose boast is that they are natives of North Carolina … attempt to dictate to the NAPA as to distinctions in color when admitting members, we feel like sitting upon them with considerable force. Carr, Daniels [i.e., North Carolina amateur journalists George M. Carr and Frank or Josephus Daniels] and the other ignorami of the contemptible state they seem proud of, may consider if 'chivalry' to exclude from association a boy who knows four times as much as any of them, simply because he is not of the same color. But it is the same kind of 'chivalry' which shoots a man in the back for a fancied insult, the 'chivalry' of a coward, the 'chivalry' of a man who is mean as he is contemptible. And while the National [Amateur Press Association] is sorry to wound the 'honah' of these young men, it will go into the business of wounding 'honahs' if by so doing it can drive such as the Carrs and Daniels from its fold and admit the Clarkes—for thereby in exchange for demagoguery and lack of brains, it receives sense and energy."

Herbert Clark ended his publication of Le Bijou sometime after June 1880, the date of the last extant issue held in the Library of Amateur Journalism Collection at the University of Wisconsin. Le Bijou was mentioned as suspended in the June 1881 issue of the Amateur Review. In 1882 Clark became deputy sheriff of Hamilton County, Ohio and worked to enforce the law during the Cincinnati Riot of 1884. He also started a professional paper titled the Afro-American; no extant copy has been located. (Source: "An Era of Civil Rights" Palladium (Cincinnati), May-June, 1887, p. 55+.) In 1883 he married Leanna C. Young, an African American woman from Louisiana who boarded with the Clark family while attending school in Cincinnati; she became a music teacher. In 1887 Herbert Clark later worked as a "gauger" (tax collector) for the Internal Revenue Service in Cincinnati. He is listed in the 1900 Census as living in Colombia, Missouri working as a teacher, and according to an article about the whereabouts of former amateurs in the June 1906 issue of The Fossil, Clark was the principal of Frederick Douglass High School in Columbia; however, this information was out of date by the time of the article's publication. In 1905 Clark was listed in The Register of Civil, Military and Naval Service from 1905 as a mail carrier working in Muskogee, Oklahoma. An article by Clark's fellow amateur journalist and editor of The Single Tax Review Joseph Dana Miller appearing in the Spring 1905 issue mentions that his old friend Herbert Clark was currently the publisher of the only Afro-American daily newspaper in Muskogee, Oklahoma. According to Winifred Gregory's American Newspapers, 1821-1936 (1937) and the more recent source African-American Newspapers and Periodicals (1998), The Daily Search-Light was the only African American daily published in Muskogee in 1905. The extant issues of The Daily Search-Light held at Oklahoma Historical Society (and available on microfilm at the Wisconsin Historical Society) do not mention Clark by name; rather, F.J. Gordon is listed as the editor, although it is possible that Clark might have been a partner in the Searchlight Publishing Company. Clark is listed in the 1910 and 1920 censuses as an accountant working in Muskogee. Herbert Clark died August 4, 1921.

Herbert Clark's younger sister Consuelo (pictured to the right) graduated from Boston University with a medical degree in 1884. She married William R. Stewart ca. 1890; she died of pernicious anemia April 17, 1910, in Youngstown, Ohio, having earlier been committed to an insane asylum in Perry, Stark County, Ohio.

Herbert Clark's younger sister Consuelo (pictured to the right) graduated from Boston University with a medical degree in 1884. She married William R. Stewart ca. 1890; she died of pernicious anemia April 17, 1910, in Youngstown, Ohio, having earlier been committed to an insane asylum in Perry, Stark County, Ohio.

Herbert Clark's older sister Ernestine became a composer and music teacher. She wrote the Bijou Polka in 1879; access an image on the Hathi Trust site provided by of the University of Michigan. Ernestine married John S. Nesbit; like Consuelo, Ernestine died of pernicious anemia in Saint Louis April 10, 1928.

For more information about Herbert Clark and his fellow amateurs, see:

- Herbert Clark, "A Drop of Black Ink" Ink Drops 10 (June 1904) Fargo, N.D.: Alson L. Brubaker, 1904.

- Lara Langer Cohen. “The Emancipation of Boyhood: Postbellum Teenage Subculture and the Amateur Press” Common-Place, v. 14, no. 1 (Fall, 2014).

Paula Petrik, "The Youngest Fourth Estate: The Novelty Toy Printing Press and Adolescence, 1870-1886" in Small Worlds: Children & Adolescents in America, 1850-1950. Lawrence, Ks.: University Press of Kansas, 1992, p. 125-142.

Faith. Graduating Essay. By Consuelo.

Excerpted:

There is not a feeling of peaceful security, not one happy moment we enjoy which does not spring from a firm faith in humanity and nature at large. There is no misfortune, no sorrow we may experience which does not result from a misplaced confidence or faith betrayed.

Faith is the very center-pin of our existence round which revolve our minor virtues and upon which they all depend.

In all the business pursuits of every day life faith is a most important element. Without it, agriculture, manufacturing and merchandising would fall paralyzed. …

If we all were distrustful, how sad would be the condition of the world.

We would see the loving, trusting heart, stirred by bitter hate and jealousy, the calm, serene brow, ruffled by anxious watchfulness and challenged Virtue disheartened yield to Vice. …

Let us all have faith in humanity to believe that no such state of affairs may ever come to pass. For we may trust in God or gods, in nature or man, to fortune or luck, to anything; but trust we must. For depend upon it, it is better to die trusting than live distrusting.”