Reporting and Reporters |

Visual Culture |

The Illustrated Press |

The Home Front |

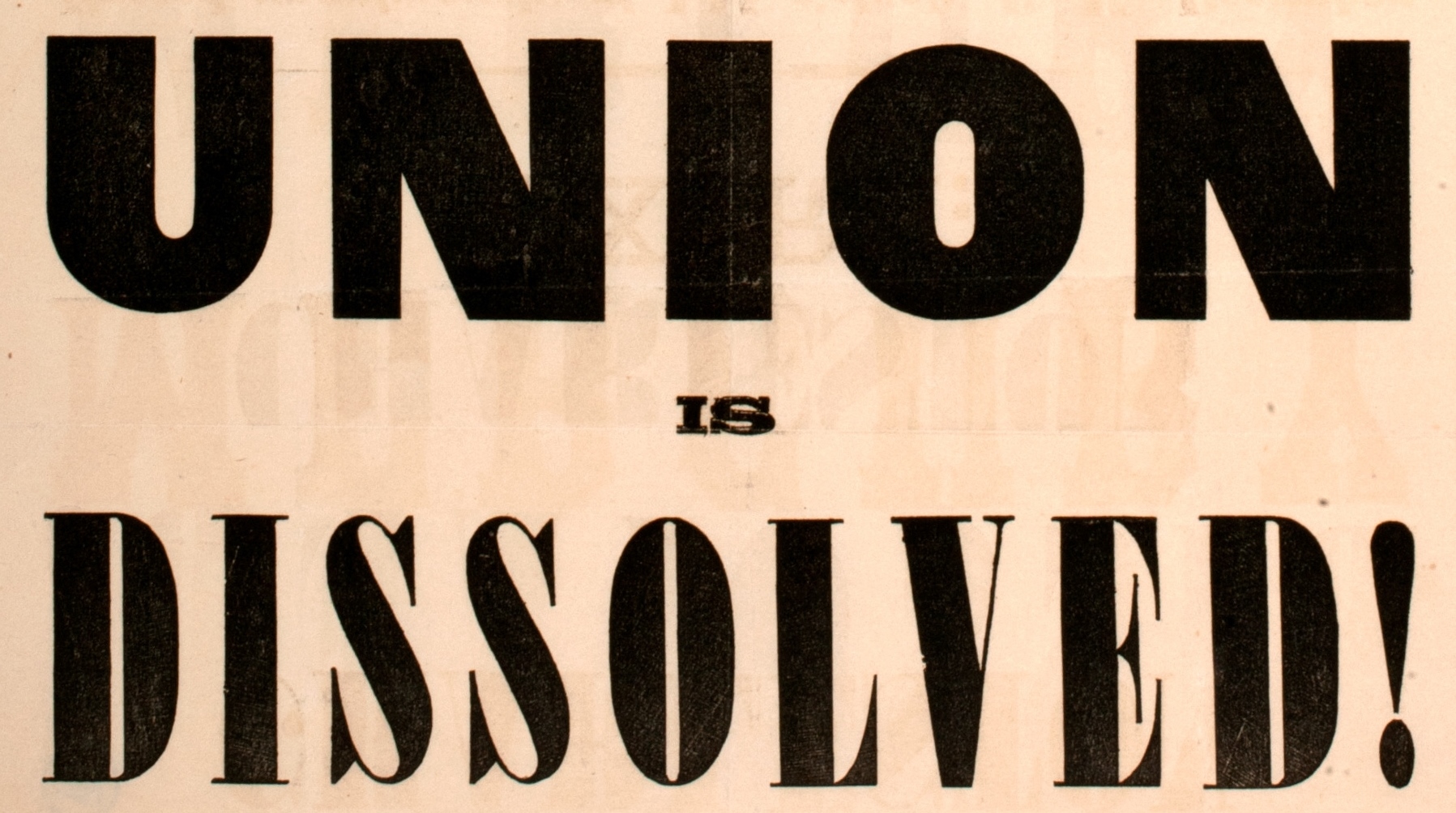

For American journalism, the Civil War era was more of an apotheosis than a revolution. In the hothouse atmosphere of war, innovations already under way in technology, business organization, professional practice, government relations, and even reader interest burst into full flower. The legacy of the Civil War includes the modern mass-circulation daily newspaper, the national illustrated weekly newspaper, and the obsession of readers for both. The war also reinforced the vast disparity of access to media between the North and South.

The telegraph and the railroad, which had been developing rapidly since the 1840s, blossomed during the war. They dramatically transformed how armies conducted warfare and how newspapers and magazines conducted journalism. For the first time yesterday’s battle news could be published in today’s newspaper or next week’s illustrated weekly. But other technologies came into play as well, including bigger, faster printing presses. By 1860 the New York press manufacturer R. Hoe & Company was producing type-revolving “Lightning Presses” that turned out twenty thousand impressions per hour and could employ curved stereotype plates. In 1861 the New York Herald topped one hundred thousand in daily circulation. With distribution by rail, the New York Tribune’s national weekly edition achieved a circulation of more than two hundred thousand. The Civil War was also a visual news story, with the dramatic growth of weekly illustrated newspapers and the popularization of photography.

Newspapers and illustrated weeklies became large-scale manufacturing enterprises in the 1860s, presided over by famous editors and publishers such as James Gordon Bennett, Horace Greeley, and Frank Leslie in New York, who embodied the public persona that would later be dubbed “press baron.” Nearly as famous—though often still pseudonymous—were the battlefield news reporters, who helped to define the role of “reporter” as a journalistic profession. On the home front, readers were enthralled by the news more than ever before. In addition to regular daily editions and “extras,” newspapers posted updates on bulletin boards, almost hourly at times. In an 1861 Atlantic article, Oliver Wendell Holmes captured the new compulsive news habit: “This perpetual intercommunication, joined to the power of instantaneous action, keeps us always alive with excitement . . . . Only bread and the newspaper we must have, whatever else we do without.”

The lust for news was the same for readers in the North and South, but the news industries of the two regions were vastly different. In 1860 less than 10 percent of the nation’s printing establishments were in the South. The South had 70 daily newspapers in 1860, out of a total of 387 nationwide, but those papers accounted for only 10 percent of the national circulation. And only about 20 dailies survived to the end of the war, in part because the South had only a handful of paper mills and no printing-press manufacturers. On the day after the bombardment of Fort Sumter in 1861, the New York Herald printed 135,000 copies, about the same as the entire circulation of all the daily newspapers in the South. The Civil War strengthened a comparative advantage in publishing in the North, especially in New York City, that would continue for more than a century.