The Early Nineteenth-Century Newspaper Boom |

Reform Movements and the News |

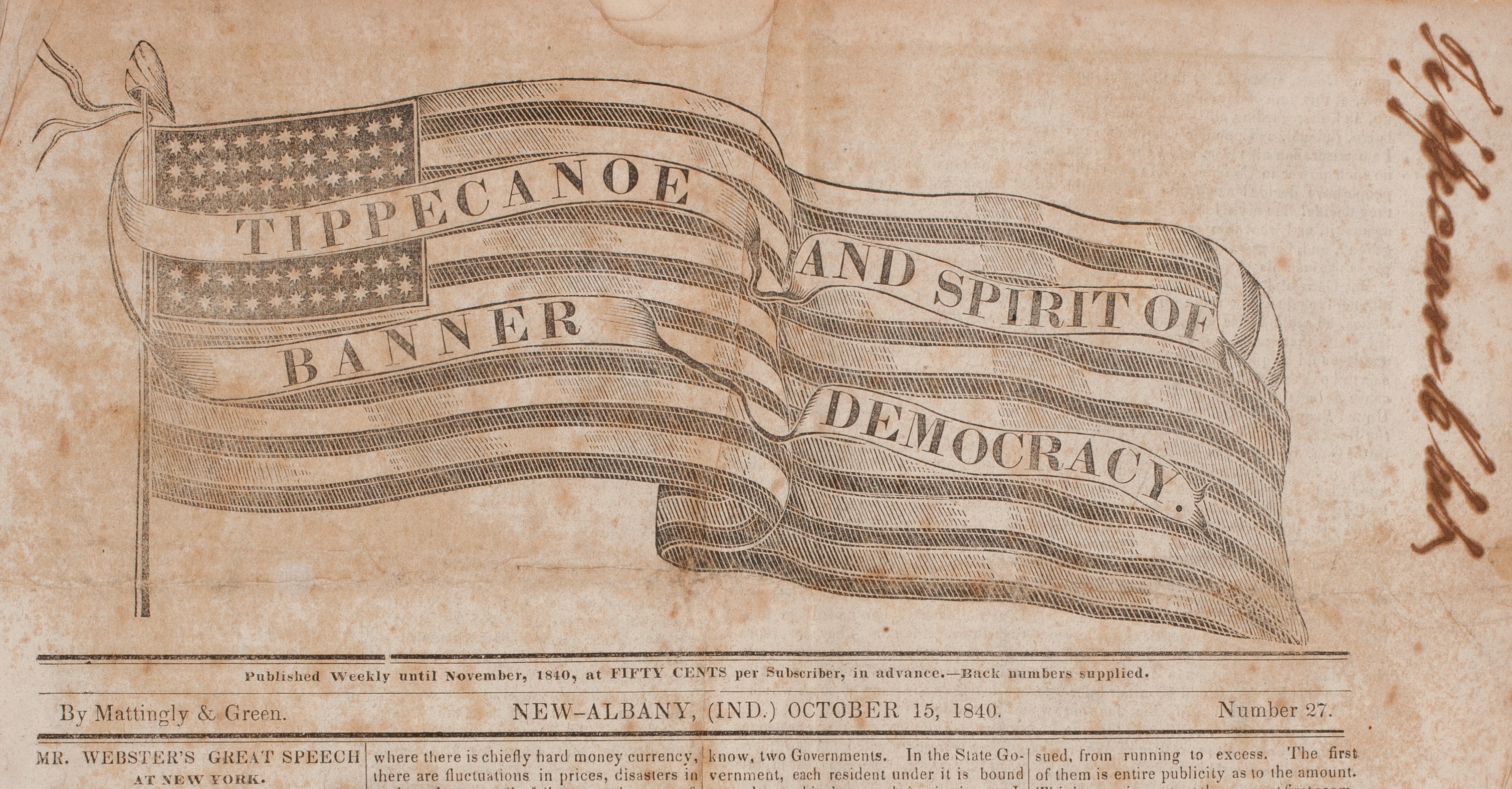

In the popular imagination, the communication and transportation revolution in early nineteenth-century America is a story of technology, of steam power and electricity: steamships and steamboats, steam-powered railroads and printing presses, and the electric telegraph. These new technologies were indeed important in speeding up the movement of people and information in the decades after the end of the War of 1812. Other new communication technologies could be added to the list as well, such as new processes for creating pictorial images: lithography and photography. All of these new technologies contributed to the development of a public communication environment in America by 1860 that deserves the modern label “mass media.”

But some scholars have argued that technology was not the most important driving force behind the revolutionary developments in communications in the nineteenth century. More important were government policy and business organization. The crucial policy decision was the creation by the new federal government of a particular kind of postal system that favored public information over private communication. With the passage of the Post Office Act of 1792 the newspaper was turned into a vehicle for national long-distance civic communication. The act provided two crucial subsidies for every American newspaper: extremely low postage for circulation among ordinary readers and no postage at all for circulation among other editors. Newspapers (and later magazines) thus became a national network for news sharing and distribution.

Organizational innovation was another non-technological factor that contributed to the communication revolution of the early nineteenth century. Commercial businesses, including publishers, created new business structures in order to operate in an expanding market economy. Moreover, noncommercial organizational innovation was equally important. The early nineteenth century was the nursery of the national voluntary association. And these new national associations—religious and reform—contributed mightily to the growth of the new mass media environment.

By 1840, before the invention of the telegraph and before the boom in railroad building, the United States, with a population of 17 million, circulated more newspapers every week than all of Europe, with a population of some 230 million. Meanwhile, the American reader—and most Americans could read—also had increasing access to cheap books, magazines, and illustrations. In other words, a nation that began life in 1776 as a remote outpost on the fringe of civilization had become by 1860 the most media-rich country in the world.